The Gospel According to Google

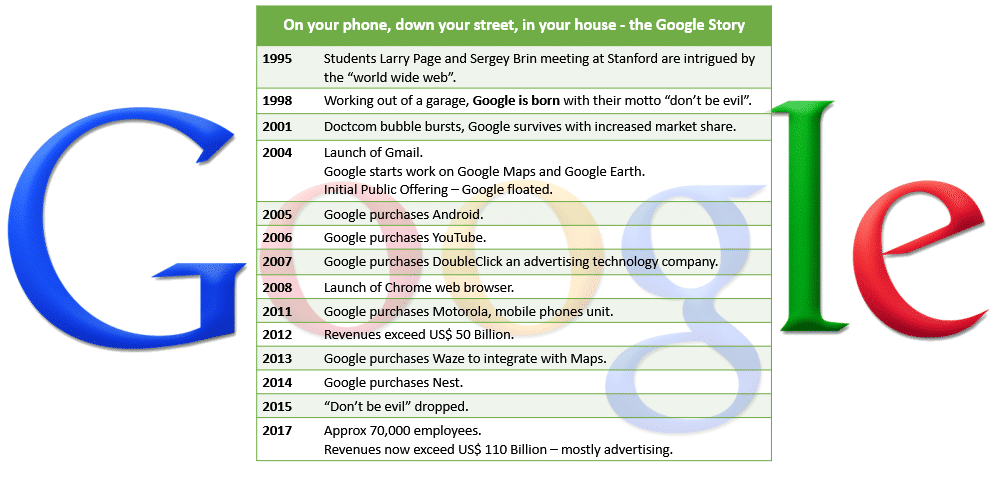

In September 1998 a tiny Silicon Valley start-up was born with a curious company slogan: ”Don’t Be Evil”. This somewhat unorthodox statement expressed a genuine intention to provide the most innovative and exciting internet products in the world, without exploiting users.

Today Google no longer tell us they are not evil. Instead the latest company motto tells us they “organise the world’s information”. That is no exaggeration. They do that — and a lot more.

We consult Google when we are buying everyday items, considering holidays, finding a job, finding a house, finding a church. Google owns Android, the software responsible for 80% of the world’s smartphones, and YouTube, the world’s largest video platform. Throw in Google’s Gmail, arguably the world’s most popular email provider, Google Maps, Google Docs etc, and we start to get the picture. This is a dominant organisation exerting enormous influence on your life and mine, every day.

![]()

But doesn’t Google just give us what we want?

We don’t want “what we want”.

Take YouTube. Like Facebook, Netflix and Amazon YouTube employs something called “auto-play”. This automatically plays the next video which the software has determined is most likely to keep you sitting there while they run ads past you. Sounds harmless – even entertaining — except that it results in countless hours wasted watching things we never set out to watch.

It’s the same with apps. Apps are the technological equivalent of sugar, leaving us always wanting more. Google’s Play Store offers 3 million apps for Android phones for every situation or whim you might have. Most are free, but the “free” business model only works if they can keep you hooked, while ads are played. Google, Facebook, Apple and co all strongly assert that they are “giving users what they want”, but it’s not what we want, not long term. Their technology prioritises impulse over intention, chipping away at whatever we set out to do that evening or that day.

Writing recently in the Financial Times, Roger McNamee (an early investor in Google but now less convinced) says “Internet platforms apply techniques of propaganda or gambling to trigger emotional responses … Facebook and Google assert with merit that they are giving users what they want. The same can be said about tobacco companies and drug dealers”.

Their technology prioritises impulse over intention, chipping away at whatever we set out to do that evening or that day

Well maybe you don’t use apps – but you do use Google Search.

What’s the harm in Google Search?

The information that a search brings back sways our decisions. Think about the way search engines offer us “auto-completion”. That’s when, as soon as you start typing into the Search box, Google starts suggesting (auto-completing) what you might be looking for. Most of us accept these suggestions, even if it wasn’t what we were going to type, we are generally lazy, easily led.

Psychologist Robert Epstein presenting at a US Psychologists conference in 2018 talks of “the Search Suggestion Effect” that search engines have. His report includes experiments carried out during the US election of 2016. To summarise this, when the words “Hillary Clinton is” were typed into Google Search, autocomplete offered phrases such as “Hillary Clinton is winning”. Yet, on the Search Engines from Yahoo and Bing, auto-complete suggested “Hillary Clinton is a liar” and “Hillary Clinton is a criminal”. Suggestions seed ideas.

Auto-complete provides just one of several powerful ways a Search Engine “manages” the information we access — and Google’s is the most popular. The mere potential to manage the information given to billions of people every day represents a remarkable level of influence.

“OK Google, answer this …”

That influence becomes even greater when we look at the new range of voice assistants including Amazon’s Echo, “Hey Siri” and “OK Google”.

“OK Google” was in the news this year as it turned out it could tell you all about the prophet Mohammed, but had no idea who Jesus Christ was. This is just one example of the need to consider carefully who is deciding what information consumers access via these assistants. A recent BBC study discovered that children commonly ask these assistants questions. Questions like: “Who are you?”, “Have you got a phone inside you?” But it won’t be long before they’re asking deeper questions … Is God real? … What am I worth? … Will I be happy? Voice assistants generally provide one answer which is pre-selected. What should that one answer be? Perhaps the church should be more involved in developing these answers in preference to the thousands of hours we invest in sermons that answer questions which, in the best case, no-one remembers, and in the worst case, no-one was asking.

Technology is “disappearing”

Of course, we need technology. In our work and our churches, it’s important to master the skills of internet research, to learn to hold a complex conversation over WhatsApp, or be interviewed over Skype. Today there is no distinction between real-world and online world, it’s all-real. But the irony, and the thing we must be aware of is that, while technology such as Google’s is saturating our daily lives, it is “disappearing”. Technology is disappearing in the sense that we no longer view it as anything distinct. We access our smartphones like we used to access a pen, no need to think about it. And we Google things we want to know as our first recourse, no need to think about it. These tools have become a natural extension, an outsourcing, of our brain.

This is why we fail to notice the increasing creep that an organisation like Google has in our lives. Did you know for example that Google holds more information about you than Facebook? Unlike Facebook Google doesn’t sell it on to third parties (like Cambridge Analytica). But they do use it to keep you watching ads. The ad funded model of the internet is largely responsible for its toxic effects, and until we accept the idea of paying for internet services, this won’t change.

So, is Google becoming an idol?

Google remains a remarkable organisation that has made astonishing leaps forward in technology in just twenty years. They employ some of the most talented and dedicated people in the world, they push the boundaries of innovation, they constantly ask, “why not?” They also direct their formidable brain power at some worthy causes. For instance Google’s Project Loon Loon will bring internet connectivity to the world’s poorest, most inaccessible, areas by beaming the internet down from – balloons. “Loons” are made from sheets of plastic the size of a tennis court floating 5 miles up in the stratosphere where the temperature is ‑90. This red-hot technology in the coldest places on earth is a key business enabler for micro businesses in developing countries. For example it allows people to determine market prices when deciding where to take produce, and to transfer money mobile to mobile while never owning a bank account.

At the same time Google’s influence has reached bewildering heights and has led to misuse, not least in the eyes of the EU who have fined them for promoting their own companion websites at the top of Search results, and most recently, for forcing phone manufacturers to pre-install Google’s own Browser and Search Engine on new phones.

The mere potential to manage the information given to billions of people every day represents a remarkable level of influence

Google influences every home in the land. Google is present on almost every laptop, phone, and increasingly our home appliances, giving them a level of “omnipresence”. Their stated company mission is to store all the world’s knowledge, which starts to sound like “omniscience”. And if we consider that, in today’s personal-information economy, knowledge is power, we could add “omnipotence”. Well we just described Google using three words we normally reserve for someone else.

Does that make them an idol? Obviously, nobody worships Google, that would be silly. But you don’t need to. Isn’t an idol simply the authority we turn to most often, the central one we depend on to answer all our questions? In our daily decisions great and small, I wonder if we seek God’s input on matters as much as we do Google’s?

This post is based on an original article that appeared in the September 2018 edition of Premier Christianity Magazine.

A separate article entitled Google Reaches 20 — Is It Now Playing God? was also published on IT Pro Portal

[…] Now check out the blog and magazine article. […]

Astonishing the reach Google now has in our lives, considering it didn’t exist 20 years ago. Of course, much of this is incredibly useful. But it clearly raises ethical questions, and has been instrumental in influencing behaviour of generations who’ve grown up with it (I was surprised to learn earlier this year that Youtubing is the most popular activity for teenagers, for instance). Like all technologies we need to think carefully about how we use them. Of course, for Christians, this carries a faith perspective which you’ve helpfully raised here.

Thanks Paul — so the most popular activity for teenagers is effectively handing over their personal tastes, habits, likes and dislikes to Google. Yes we should be a least a little concerned.

Thank you for highlighting these important issues Chris. Technology is such an intrinsic part of our lives and we have to think clearly as to what are appropriate limits and boundaries. Unfortunately we can so easily just accept what is presented to us without any discernment. Very helpful and illuminating issues you raise.

Thanks Sunil for commenting

Wow

Spooky stuff, loved this

🙂